Coal

For details of mining in and around Bathgate see

The Bathgate Book page 122

Types of Coal

From

Dictionary of Mining, Mineral, and Related Terms

Compiled by the American Geological Institute

Boghead Coal: A variety of bituminous or subbituminous coal resembling cannel coal in appearance and behaviour during combustion. It is characterised by a high percentage of algal remains and volatile matter. Upon distillation it gives exceptionally high yields of tar and oil. [Also called Bathgate Coal. Boghead Coal is about 315 million years old. At this time the area that is now Bathgate lay a short distance north of the equator. The coal was formed from algal mud deposited in a warm lake covering about 3 square miles which extended from Bathgate to Tippethill. It was from this coal that James Young extracted oil in his Bathgate refinery. Boghead coal is richer in oil than cannel coal. David Bremner in The Industries of Scotland [page 9]says that Boghead coal gives 120 gallons of crude burning oil, or 15 000 cubic feet of gas per ton. ]

Boghead Cannel: Cannel coal rich in algal remains.

Boghedite: Torbanite

Cannel Coal: Term used for sapropelic coal containing spores, in contrast to sapropelic coal containing algae, which is termed boghead coal. Analogous term is parrot coal. [Cannel coal means ‘candle coal’ because it burns like a candle. Sapropel is mud rich in organic matter.]

Bitumenite: Cannel coal from Torbane, Scotland. Also spelled bituminite.

Bathvillite:, An amorphous, opaque, very brittle woody resin; forms fawn-brown porous lumps in torbanite; at Bathville, Scotland.

Torbanite:

- A variety of algal or boghead coal from Torbane Hill, Scotland. It is layered, compact, brownish-black to black in colour, very tough, and difficult to break. On distillation, torbanite gives a high yield of oil. Also called bathvillite. Syn: Torbane Hill Mineral.

- A dark brown variety of cannel coal.

Bituminous Coal: The most abundant type of coal. It is brown to black in colour and it burns with a smoky flame. It has a relatively high proportion of gaseous constituents. [When heated in the absence of air it gives a variety of products, e.g., coal gas, tar, ammoniacal liquor, ash, coke. It is sometimes called common coal.]

Anthracite: A hard, black lustrous coal containing a high percentage of fixed carbon and a low percentage of volatile matter. Burns with a short blue flame, without smoke.

Other names

It often happens that coals are given names relating to their uses or properties, e.g.:-

gas coal: Gives off a high volume of combustible gas when heated in the absence of air. Boghead and cannel coal are good gas coals.

coking coal: Bituminous coal from which the volatiles have been driven off by heat, so that the fixed carbon and ash are fused together to form coke.

caking coal: Coal that softens and sticks together on heating. Produces a hard grey cellular mass of coke. Caking coals do not all produce good coke.

steam coal: Coal suitable for use in boilers. It is low in volatiles so does not produce much smoke.

parrot coal: A bituminous coal rich in volatiles which ignites easily and burns with a crackling sound supposed to be similar to the squawking sound made by a parrot.

smiddy coal: Smokeless coal suitable for use by blacksmiths.

house coal: Bituminous coal burned to keep homes warm. Burned in this way it gives off lots of smoke which causes air pollution and smog. Thick chimney smoke gave Auld Reekie its name.

Miners have many terms to describe coals and other rocks, e.g.:-

burnt coal: Coal which has had its volatiles driven off by an igneous intrusion.

blind coal: A type of anthracite

cherry coal: Shiny, freely-burning coal

free coal: Coal which breaks or burns easily

rough coal: Type of inferior coal

splint or splent coal: A hard laminated variety of bituminous coal. It splits into slabs. Burns without caking.

short coal: Coal with wide joints in the seam.

wild coal: Poor quality coal.

blaes: Clay or carbonaceous shales of a bluish colour.

Fakes or faikes: Rock which is partly sandy and partly clayey. Fissile sandy shales or shaley sandstones.

faky blaes: Blaes with partings of fakes.

maggie: Poor quality ironstone.

blackband ironstone: Ironstone which contains enough carbon to make it self-smelting.

daugh: Coaly fireclay. Soft fireclay.

From

Mining the Lothians by Guthrie Hutton

P14-17

Geologically, West Lothian was part of the Lanarkshire coalfield and the county’s pits were included in the area covered by the Lanarkshire Coalowners’ Association. The NCB perpetuated the link by placing West Lothian pits, with the exception of those at Bo’ness, in the Central East Area and running them from Shotts. Easton pit at Bathgate was one of the county’s most successful units. At one time Bathgate railway yard served over forty pits and was one of the largest in Scotland.

Easton was linked to the older Balbardie pit which tapped the rising seams to the north of the town. The colliery was being worked by Walker and Cameron in 1895 when two of its six boilers burst, killing two men and injuring a third.

Easton’s principal seam was the Wilsontown Main. It was between 5 and 8 feet thick, but had bands of dirt and stone up to 18 inches thick running through it. Large quantities of stone, dirt and bits of coal ended up on the enormous bings. The pit was due west of Bathgate and the bing’s sulphurous fumes were borne by the prevailing winds across the town.

Sinking at Easton, known originally as Hopetoun colliery, was begun in 1896 and coal was reached at just over 1 000 feet two years later. The pit was sunk by the Balbardie Colliery Company, who had taken over from Walker and Cameron. They in turn were taken over in 1907 by William Baird and Company (Baird’s and Scottish Steel from 1939), one of the giants of the Lanarkshire coal and iron industries. In the 1950s the NCB electrified the winding engine and constructed a new washery.

In 1962 the NCB categorised pits according to their future prospects: Category A was for pits with prospects, if reserves were realised; B pits had reserves, but an uncertain future; those with a C rating had little or no future. Easton was category A. It was still an A at the next review in 1965 and in the following year was given an unlimited life of 15-20 years (!). Within four years, however, extensive faulting of the field made machine mining impractical and the pit closed in July 1973.

On page 17 are copies two adverts for mining equipment made by

The North British Steel Foundry, Engineers and Blacksmiths, Balbardie Steel Works, Bathgate, N. B.

- Makers of hutches and corves of all kinds. Wheels and axles. Pedestals, platform crossings, horse crossings, mouthplates, turn-tables, pulleys, bevels, rollers, haulage clips, jigger couplings, gearings, machine moulded or machine cut, elevator buckets, and castings and forgings of all descriptions. Machined and finished complete.

- Makers of cages of all descriptions with and without tilting bottoms, fitted with any type of controller, rope hoses, haulage gears, tub oilers, and mining plant of all kinds.

From

Guide to the Coalfields 1949

P58

N.C.B. Scottish Division Area No. 4

Bathgate/Forth Sub Area Production Manager William Rowell, B.Sc.

Tel.: Bathgate 404

HOPETOUN, Bathgate, West Lothian. Tel.: Bathgate 6.

Coal: Gas, manufacturing & steam. Seam: Wilsontown Main. Electricity used underground. Men employed 1948: above ground: 140, below ground: 401

Agent: T. Blair Interim Manager: P.J. Weir Undermanager: A. Miller

Inspectorate: East Scotland District

From

Guide to the Coalfields 1962

P32

N.C.B. Scottish Division, Central Area

Group No. 1: Group Manager: R. Finlay, Polkemmet Office Whitburn.

Tel.: Whitburn 304/7

Group Electrical Engineer: R. Bain Group Mechanical Engineer: R. Brown

EASTON, Bathgate, West Lothian. Rly.: Bathgate Tel.: Bathgate 2393/4.

Coal: Gas, manufacturing & steam. Seam: Wilsontown Main. Men employed 1961: above ground: 146, below ground: 590

Manager: D. Munro Undermanager: M. Mackinnon

Inspectorate: Scottish S.E.

From The Rocks of West Lothian by H. M. Cadell 1925

P214

The Bathgate Coal-field

The south-western corner of the county, mainly within the parishes of Bathgate and Whitburn, includes the most extensive coal-field in West Lothian. We have here, two distinct coal-bearing series of rocks. In the lower of these, of Carboniferous Limestone age, the coal seams are all below the Index Limestone. The Bathgate coals in this position have been proved by bores and pits to exist in good condition under the Millstone Grit and the Coal Measures, more than two miles westwards from the outcrop. Some of the existing workings have reached a depth of about 200 fathoms below the surface, and still deeper extensions are in progress at Whitburn in the new colliery of Wm. Dixon, Ltd., where the Bathgate or Wilsontown Main Coal has been found in good condition at 237 fathoms. The upper series above the Millstone Grit represents the edge of the true Coal Measures which extend westwards into the Lanarkshire field.

In this chapter we shall look at the Limestone group. The lower limestones and the coal seams above them dip steadily to the west, and the comparatively straight outcrops are broken by few faults of any size. The strata along the line of the Bathgate ridge have a comparatively steep dip of 20 or 25o. As the strata are followed downwards the angle diminishes and the beds slope gently towards the centre of a flat broad basin underlying the Millstone Grit and the Coal Measures.

Beginning at the north end of the coal-field we find the first representatives of the coal seams at Kipps on the high-ground three miles north of Bathgate. The Sheriff Court records, which have been lately examined by Mr James Beveridge, show that coal was worked at Kipps in 1640 by a miner, William Cowie by name, who, with a partner, had a lease of the coal heugh from Mr Robert Boyd of Kipps. Sibbald, writing in 1710, mentions the coal on his estate of Kipps which had been worked at the outcrop at that date. Forsyth, in 1846, refers in greater detail to the attempts that had been made to mine the coal in his time. He says that a pit had been recently sunk to the Kipps seam in which so many faults were met with that it soon had to be abandoned. There were here several thin seams and a thicker one of 33 in. with 3 in. of Parrot coal below it.

The coal seams were found at the outcrops both at Kipps and Cathlaw, and were used in olden times mainly for burning limestone. Mention is made of the coal on the west side of Cairnpaple in the Old Statistical Account, when the working was going on in 1792, and this apparently refers to the Hilderston Hills Colliery. No doubt the close proximity of the coal enabled the limestone on the Bathgate Hills to be extensively quarried at a time when the means of transport were very primitive. The numerous ruins of limekilns show that the lime was burned on the spot, and even inferior coal could be mined with advantage for this purpose.

At Hilderston Hills, 1.5 miles south of Kipps, we find the coal under the Index Limestone reappearing in increased dimensions. A small colliery was carried on here for many years, but the coal was not of best quality, and the field was abandoned. [The Limestone Coal Group lies under the Index Limestone. If you found the Index Limestone in bores or pits you knew that you would soon reach good coals. Index means indication or sign hence the name of this limestone.]

The Old Statistical Account states that in 1791 the deepest working had reached 40 fathoms in Bathgate Parish, twenty miners were employed, and the pits supported ninety-five people in all. The great increase in the population of the parish since 1750 was chiefly due to the collieries, and the writer remarks, ‘to which cause, also, must be attributed the great influx of poor into the town and neighbourhood.’

The Main Coal, being the thickest seam, was at first sought after. Half a mile south of Hilderston there were at Ballencrieff numerous old pits in 1847, including a stair pit of ancient date and a pumping pit 47 fathoms deep which had been in operation for more than a century. Here the Main Coal was from 5 to 6 ft. thick with two ribs of stone, and was worked in pillars. The Balbardie Gas Coal, a short distance below the Index Limestone, makes its appearance in workable condition at Hilderston Hills Colliery and at Ballencrieff. To the south of Ballencrieff Pit two dip faults cross the outcrop at right angles, and beyond these, a mile south of the Hilderston Hills, we reach No. 1 Pit of Balbardie Colliery 49.75 fathoms to the Main Coal where the coal section has further improved and three workable seams have been reached, the Balbardie Gas, Jewel, and Main coals respectively. [Dip fault: The beds are displaced down the direction in which they are dipping.]

West of Bathgate the field is being worked by Messrs Wm. Baird & Co., Ltd., in the Balbardie Easton Pit, a mile west of the outcrop of the Main Coal at Bathgate. The Main Coal is here a little more than 200 fathoms deep. The Jewel seam is also being worked. The field is here clean and regular with few faults and a moderate dip.

In the original Balbardie Pit No. 1 near the outcrop, the Balbardie seam was chiefly valuable on account of its Parrot Coal and Ironstone. The Balbardie Parrot was a gas coal of exceptionally high quality and was associated with a band of good Blackband ironstone. As a gas producer, the Cannel was about the best in West Lothian and one analysis gave 49.2% [by mass] of gas, tar and other hydrocarbons. One ton gave 14 150 cub. ft. of gas with an illuminating power of 36.42 candles and 1094 lb. of coke of fair quality. The ironstone was formerly worked along with the coal at Boghead and Moss-side Collieries, as well as at Balbardie and Easton, and its thickness occasionally reached 6in. [Candle: light given off by an ordinary wax candle]

The original section of the seam at Balbardie was as follows:

| Rock | Feet | Inches |

| Gas coal | 3 | |

| Cannel coal | 6 – 11 | |

| Blackband ironstone | 3 | |

| Fireclay with ironstone balls | 1 | 1 – 10 |

| Free coal | 1 | 3 – 6 |

The Main Coal was worked under Bathgate before 1840 and the Old Engine Pit, 30 fathoms deep, was at the east end of the burgh. Here the dip was about 20o.

The ground to the south of Bathgate has now been thoroughly explored and there is now a line of collieries extending for five miles from Bathgate to the Breich Water along the whole outcrop. Boghead Colliery is the most northerly of these. The Main Coal, which has at the pits a dip of about 25o, has been followed westwards in the workings for two-thirds of a mile to a depth of 200 fathoms, where the strata become much flatter. To the south-west, the Bathgate Main Coal is known as the Wilsontown Main and the Bathgate Jewel as the Lady Morton Coal. At the north end near Bathgate there have been four deep borings:

- Moss-side bore on Wester Inch estate which reached down to the Top Hosie Limestones. [The Hosie Limestone is about 500 feet below the Bathgate Main Coal.] It was made by Messrs Gavin Paul & Sons in 1904.

- Henry Walker’s bore made at Boghead Colliery, Little Boghead.

- Vivian’s bore from the base of the Coal Measures, 700 yards west of Walker’s bore. [The Coal Measures lie above the Millstone Grit. The Millstone Grit lies above the Carboniferous Limestones.]

- Boghead bore, by Messrs Wm. Baird & Co., Ltd., near Boghead House, made in 1912, 265 fathoms in depth.

Some details of the Bathgate coal-field are as follows:

Section at Boghead from base of Coal Measures:

On the Torbanehill Mineral by Thomas Stewart Traill

Paper read to the Royal Society of Edinburgh 5th December, 1853

I had been requested to examine the mineral in its native bed; and, accordingly, went to Torbanehill, and saw the works. There were four pits or shafts, but No. 1 was no longer wrought; Nos. 2. 3. and 4 were in active operation, and large blocks of the mineral lay around the mouths of these pits. The blocks varied in thickness, from 1 foot 4 inches to 1 foot 11 inches.

I descended into No. 2. The depth of the shaft was 17 fathoms. From the bottom of the shaft, a drift was carried for 80 yards, in a northerly direction, with a dip of about 1 in 12, almost half-way between No. 1 and No. 3. {This puts the depth of the Boghead Coal at about 120 feet.}

In descending, the succession of the strata are:-

- A thick roof of sandstone.

- Faeks, a crumbling shale = 4 inches in thickness. This bed in No. 3 is wanting; but it forms the roof in No. 4.

- Cement, a mixture of shale and poor ironstone = 3inches in thickness.

- Bitumenite {i.e., Boghead Coal} which is in this pit at the /~&? = 1 foot 4 inches in thickness.

The Bitumenite seems to be thickest near the top of the field, as in No. 4, and to diminish a little in thickness in the other two pits.

According to the OS 1856 map, No 2 was worked out as well when surveyed in 1854.

The map also features Torbanehill Nos 6 and 7 – but no mention of No 5.

The Coal-Fields of Scotland by Robert W. Dron 1902

Page 197: John J. Landale says of the Boghead Gas Coal that it ‘has the peculiarity of thickening and thinning…’

He gives two thicknesses from Boghead : 4 inches and 8 inches; and two from Torbanehill – 1 foot 6 inches and 2 inches.

Text

From:

The Mineralogy of Scotland

By M. Forster Heddle 1901

Volume 2

P188

Torbanite

Torbanite, although related to cannel coal, has a very nearly uniform composition, according to all analyses thus far made, and this composition is like that of bathvillite, but with less oxygen. It corresponds very nearly with the formula:

C40H68O2.25

By weight, this equals carbon 82.19; hydrogen 11.48; oxygen about 6.0; nitrogen 1.37 = 100%

Less than 1½% of torbanite is soluble in naphtha.

In Upper Carboniferous rocks, at Torbane Hill, Bathgate Parish, Linlithgowshire.

‘It frequently occurs in seams of some considerable size, and always in the neighbourhood of coal, sometimes in intimate contiguity with it, but at other times …separated from it by a layer of fireclay.’ The colour varies from tan colour to sooty-brown. Its fracture is dull, and often conchoidal, like that of cannel coal, and it is translucent in thin section. ‘Its specific gravity ranges from 1.2 to 1.3.’ Its streak varies in colour from saffron to umber, and is usually shining, and very similar to that afforded by oil shales. ‘It is tough, and not so brittle but that thin sections may be made of it.’ It possesses considerable elasticity, and, ‘when struck by the hammer, it emits a dull sound. The remains of plants, especially of Stigmaria, [Roots of tree-like plants such as Lepidodendron.] are of constant occurrence… Under the microscope it is found to consist of masses of a yellow material , some being of irregular figure, others more or less rounded, embedded in a granular matrix, which vary in colour from a yellowish-black almost to a black.’

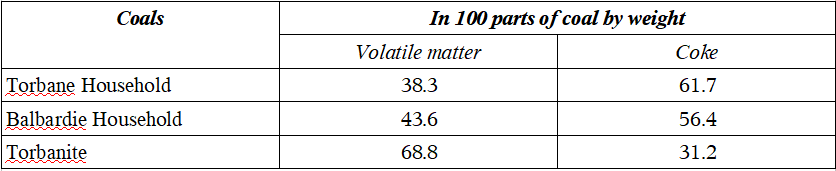

The table shows the composition of torbanite compared with local household coals:

P190

One ton of torbanite gives 15 480 cubic feet of gas. No other coal produces as much. The next best gas coal is Capeldrae from Fife. It produces 11 500 cubic feet of gas per ton. Torbanite is also the most valuable coal. For example, it is nearly twice as valuable as Capeldrae gas coal and nine times more valuable than Leven (Fife) splint coal.