By Euan Dunsmore

Recently I was asked what it was like as a Bathgate bairn living in post-war Scotland. Memories were unearthed and here are those of that most important of human needs, food. It’s type, quantities, sources, and preparation.

Our first strong memories shine brightly among the background good or bad. The background determined by the comfort or discomfort of the home. War time and the aftermath was my background, a time of shortages and rationing of food, clothing, furniture and others. Coal, the fuel for the country, was not rationed per se but its use was limited and controlled. Was I aware of this? Dimly, but becoming noticeable as time moved into the 50s and beyond. Things did improve with rationing ending in 1955. I now know the Ministry of Food and the government worked desperately hard to ensure all were served equally for the public good.

It was about this time various boards were set up to help maximise food production, potatoes, eggs with the little lion stamp, etc.

Bread and potatoes were not rationed and made up for the strict limits on other foodstuffs. Certain other home grown vegetables were freely available and most folk would grow what they could if they had a garden. It was a time of folk having bantam hens in their backyard for eggs.

As the war ended, I reached the first adventure of primary school. Hunger was never part of my life, I was fed as was my sister and as bairns we only know what we live through. Dad was a miner for the duration of the war and a few years after and we lived a country sort of life with a farm as a neighbour. The mixed memories of good days and bad seldom include food yet some words or some pictures evoke those memories and it becomes clear the menu of that difficult time of the war and its aftermath.

Being a miner, Dad was entitled to a few more food rations to compensate for the extreme hard labour of life underground as were other workers. The government was at its best where management of food was so important. There was no difference in class or status. The rich, of course, could always find extra, black market whispered.

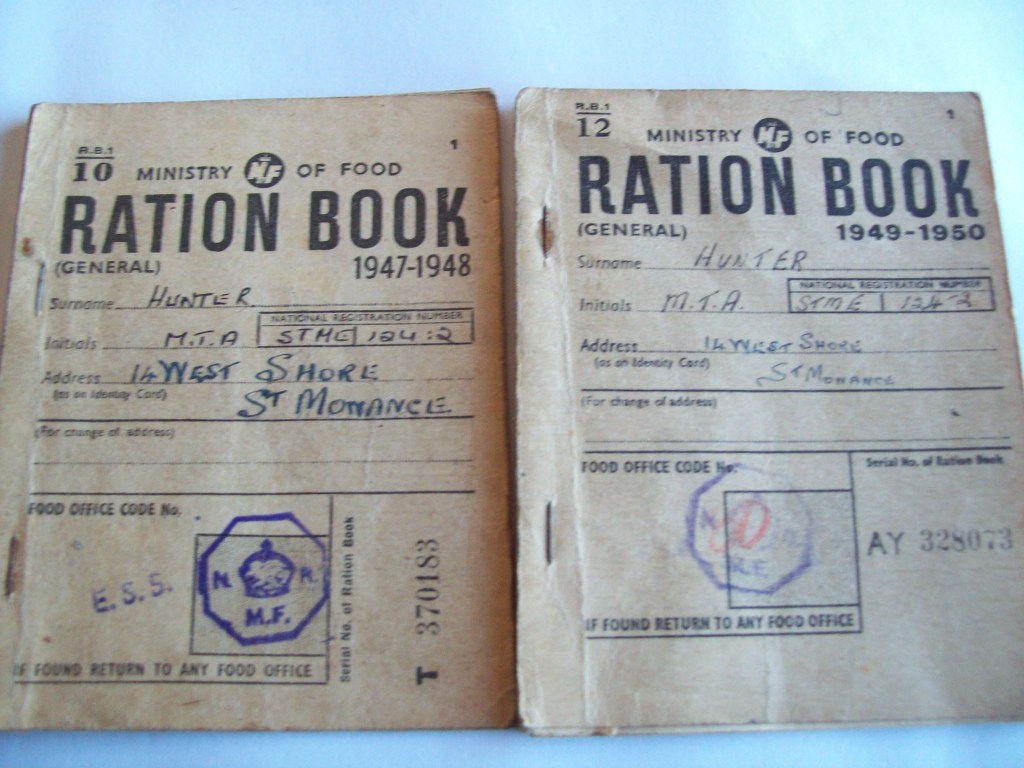

Ration books were issued every year by the Ministry of Food (MoF) for all sorts of supplies and issued in the COOP hall. I was tasked to get ours from our first years in Athol Terrace in 1949 to the last in 1954 (?). Mine and that of my sister Eunice was a different colour from those of my parents. We probably were given rations based on age.

WWI also had had rationing as I remember my Dad telling me of being sent down to the local shop and wondering why his brand-new brother James needed corned beef! My cousin Jamesina worked as a clerk in the MoF prefab offices in Gideon Street, opposite what is now a nursery.

As bairns we had some extras. Orange juice from concentrate, cod liver oil as a punishment or Scott’s Emulsion if I been good. At school, every morning there was a 1/3 bottle of milk at a cost only to the tax payer. Every bairn in the country was entitled. Every morning a couple of the boys would be detailed to bring the milk to the class. The little bottles had a small cardboard cap with a flap for the straw. The caps made a good base for making woollen pompoms. You had to give the bottle a good shake to disperse the cream. Milk was not homogenised in these days. Tuberculin testing (for bovine tuberculosis) becoming an issue for every herd. Tuberculin Tested was a sales motto for milk, reflecting the common fear of the illness killing all sorts of folk, several cousins and an auntie for me.

Milk was delivered every morning by teenage boys earning a penny from the milk man, Dan Reid of Ballencrieff or the COOP. (Dan Reid had a TT herd.) As an aside, lemonade was also delivered. Petrie’s limeade was my special ginger.

Butter was on the ration but for a special treat butter could be made. Milk was not homogenised, the top three inches in a pint bottle of milk was cream so it would be skimmed and saved. I made butter at home and at my auntie Nellie’s in Kirkaldy. A clean 2lb. jam jar, cream added, tightly sealed with the tin lid and ensconced in an old sock to be spun across the floor, rolled back and forth till the yellow butter formed. It was good was fresh butter on a home-made scone. Country folk could always get a bit of butter. My Granny sent me to the local farm with the one-pint metal jug with domed top and wire handle for milk and a pat of butter. Six I was and demanded the butter before handing over the sixpence. Without a word the dome was lifted and the pat of butter floating on top. Was it legal? She also kept hens did Gran. Dad as a boy looked after the henhouse and perhaps that was why he would not eat chicken – you cannot eat a friend. She always had eggs did my Gran. My sister had fond memories of scouring the hen-run for eggs.

Rations of fat included MoF margarine as well as lard. The margarine came in 1/2lb blocks and was a very long way from being spreadable. I swear it rang when tackled with the knife! It must have taken Mum ages to get it to cream for her baking.

I remember the first orange and now with a guilty conscience. I arrived back from school and sat down at the table while Mum peeled the pith from a large round orange ball. I remember the smell and then the first bite of glorious taste and the look on Mum’s face, later identified as longing, as I finished the last segment. Oh, how much better that big Jaffa orange tasted compared to the orange juice concentrates from the MoH bottles. Bananas have never been a favourite since I bit into the first before a smiling Mum peeled the skin. Apples, plums and soft fruits were unrationed and came in their seasons but imported fruits like oranges, bananas and grapes were rare until the late 40s. Macintosh Red apples from Canada were a revelation as British apples were not so colourful or, to me, as tasty. Seedless grapes came in the early 50s, Dad’s favourite. Every summer folks waited for the first Clydesdale tomatoes. They were tasty but the season was short. These nurseries also provided a great deal of the soft fruit, rasps and other salad stuffs and always in demand.

Shortages were, I suppose, all part of these years. At school there were scrap paper collections as well as rosehip collections for the delicious syrup that I believe was also part of the bairns’ special government diet for vitamin C. I remember collecting pounds and pounds of them. When Mum got flour, she would bake fruit loaves with what currants and raisins she could find. My paternal Granny would always have her home-made soda scones baked on the swee over the fire, never weighed, handfulls of flour, soor dook and pinches of salt. Tattie scones were also a home baked item and much better than shop-bought.

Country schools would have the tattie-howking holidays for the bairns to bring in the crop. A miserable job, back bent and mud clagging the feet. I remember once when living in Balbardie House Mum, Dad and neighbours clearing the field bordering the Torphichen road working till the moon came out. For myself it was once only at Bughtknowes Farm.

The day-to-day menu always seemed to include soup as a starter and often as the only course with bread. Scotch broth was made with a bone – bones were not rationed. Dad would dig out the marrow and slaiger it on a slice of bread. Pea soup made from dried peas and a ham bone was a special treat. It was well into the fifties before tinned soup became available. The COOP was a reliable source of the soups and tinned meals used as temporary or hurried meals. Tomato soup was a real treat.

Neeps, tatties, carrots always seemed to be available. Leeks in winter from Musselburgh and post-war the Ingin Johnny from Brittany and his bike with strings of onions round his neck added to the menu. Pearl barley always a favourite of mine to give a good feeling in the mouth. Porridge was seldom made for us as Dad hated the stuff. I liked it with salt and creamy milk. Cornflakes and Weetabix arrived soon after the war.

Mutton, or beef stewed or boiled as a lump, or that Scottish favourite, mince, were the normal meat courses along with tatties, bashed with a beetle or served whole and never with the skin on. We were told the skin was poison!. We also had carrots or bashed neeps and sometimes cabbage. I was well married before I found out cabbage lightly scalded and a couple of minutes on the simmer could actually be a nice accompaniment. In those days of old it was boiled to death and given a good ten minutes more to reduce it to a heap of watery flavourless stuff. Sometime in October the sprouts would be prepared and left to stew to be ready for Christmas. Sprouts are horrible things. I would not feed them to my pig and would be happy to leave them for the puir souls who liked them!

Every house had a chip pan with lard being the fat of choice or to be sure the only thing. Proper chips, big and fat and golden, especially with ham or a bit of fried haddie. Belfast-cured ham was our favourite and it was sliced by the butcher or grocer to your choice of thickness. Fried bread with the bacon or black pudding went well with chips. Salad days would bring corned beef, or rarely, boiled ham with a bit of cucumber and lettuce with beetroot as the pickle of choice. Mum was excellent at the sweet course – suet puddings, apple pie, duff. When tinned fruit came back to the menu it would be with custard. Rhubarb, stewed or baked as a pie was, and is, a favourite. Semolina was a favourite of mine. Rice appeared only as baked with sugar and an egg. It can be cooked as a main dish, without sugar and cream??? Never.

A great favourite was the dripping from the chops when grilled. There was a fight to be first with a scrap of bread and wiping the savoury fat from the pan and then from the lips.

Bread came from the COOP and was delivered by an electric van; Willie was the driver. It came unwrapped and uncut, every house needed a good knife to render the slices of variable thickness and shape! The heel of the Scots half-loaf made excellent toast or cheesy toast as it was usually thick enough to be stabbed to let in extra butter. Cheese was cut from the kebbuck of your choice by the grocer and my Dad loved Dunlop, a fierce-tasting cheese now difficult to source even in Ayrshire. Mum preferred cheddar. When I was about seven or so and visiting the Foulshiels Colliery canteen I was fascinated by the large slicing machine, loaf after loaf being cut to even thickness slices! Dad was a shot-firer in the pit and his piece tin was the shape of the loaf, he would have onions, or jam, with his cheese. .

Roasted cheese, a favourite supper dish with perhaps onion or tomato, every bit as good as that Italian foreign stuff, pizza.

Fish, unrationed, was not a major part of our menu, sometimes a bit of whiting, haddock, seldom cod, and always fried, with chips. Kippers did appear regularly. Sausages, mainly beef, seldom pork; in fact it was rare for Mum to have pork. I suspect it was the roasting of it that was the difficulty. We seldom had roast meat. The Ure stove in Balbardie House and the gas stove in Athol Terrace seemed not to be good for roasts although they were pressed into action for baked goods.

I was fortunate in the choice of aunties. When we went visiting, something was taken as a token towards the rations, sometimes Mum sent Dad took something baked. When we visited it would be ‘Do you fancy a pancake Wull?’ and they were good so they were, fresh from the pan with butter and perhaps a sprinkling of sugar.

I cannot remember any sort of biscuits in our house – certainly not chocolate biscuits. I do remember once when with Dad on Granpa’s coal lorry being offered a custard cream. It was horrible as the filling taste metallic. It is probable the filling was potato based with artificial sweetener. War time flavoured substitutes. Jam was extended with carrots, turnips and apples for sweetness and bulking. Jam came in 2 and 1lb jars useful empty as a substitute for money for entrance to the Cinema on Livery Street for the afternoon matinee!

Most food was fresh as it was bought on the day it was used. We had no refrigerators or freezers. At best there was a cold shelf in the larder – a 2” thick slab of stone or concrete and as houses were cold could keep meat for a day or so. Most housewives had a good shopping bag and shopped almost every day for essentials. The ration books were made up of pages with tear-off stamp-like flimsies. These would be torn off for every sale but Mum deposited some in the COOP and some in Walker,s.

Bathgate COOP was the premier shopping venue for everything from birth to death. At the butcher’s you rubbed shoulders with next week’s stew or roast, the carcases hanging from the rail making their way to the butcher’s slab. The slaughter house was in the middle of the town, as they all were in those days, and close to the gasworks. Everyone knew where their meat came from, sometimes found escaping and running to the Steelyard as entertainment for the police.

Bryce’s in Hopetoun Street was our favourite shop for vegetables. Shortages ensured there was seldom waste. As a wee boy with a ha’penny I could make a purchase of some chipped fruit. Woolworth’s had an aisle selling broken biscuits. The excitement on the finding of unbroken biscuits …

As a family we did not eat out but for those that did there was the chip shop with a few tables as well as ice-cream cafes. Greigs was the posh tea room overlooking the Steelyard. I do remember clearly being on a trip doon the waater with Dad having a most wonderful tea: Silver service with a napkin and poached salmon with salad and a fish knife. Mouth-watering it was, and still is!

My Auntie Mary had a chip shop on Main Street opposite the Simpson Memorial Hall and handy for Cringan’s, the Green Tree and the Cinema patrons on their way home from the evening entertainment. My cousin Myra and I served our time preparing for opening time on a Friday, Saturday, and Sunday. I made up the batter from powder, water, and a deal of effort. I also prepared the vinegar and brown sauce – acetic acid for human consumption, the Rowat’s liquor diluted and used for getting the sauce out of a big stone jar, almost solid in winter. There was no central heating anywhere in those days. I also heaved the tatties into the peeling machine and afterwards took out the eyes before chipping every potato, about 1 cwt per night. Black puddings and haggis puddings were skinned ready for the batter and the pans. Only lard in great big blocks were used for the frying. Myra sorted the tables and did a lot of the cleaning as well as preparing the newspapers for wrapping the servings. Davidson’s shop was the source of the unsold papers. It was years before I enjoyed a fish supper.

Things did get easier as rationing slowly disappeared. Sugar came off the ration but only for about a week after the nation emptied the sweet shops of their stock. There was a sweet shop opposite the Balbardie School, Bobby Robert’s, on the corner ofTorphichen Street and the High Street. on the day rationing ended it was a wonderland of sweets I had never heard off, Fry’s Five Boys chocolate and my favourite to be, Spangles as well as a range of boilings and toffees and I could afford them with my pennies. A week later rationing came on again! The country had eaten all the sugar!

Crisps came onto my scene with Golden Wonder’s from Broxburn sometime in the late 40s. They were not rationed but shortages affected their production and there was only one flavour for some time. Bathgate was late in the opening of foreign restaurants; we heard of curries from India and Chinese restaurants in the big toons like Edinburgh and Glasgow. The first Chinese restaurant was probably in the early 60s in North Bridge Street, up from the Beehive. Frozen foods began to appear, fish fingers, and flat things called burgers to be fried, and other exotic foods.

Celebrations were short in supply with Christmas being a celebration for bairns and the Kirk. It was a working day for all until the 60s. There was no turkey, a late addition to the country’s menu but maybe there would be a roast or steak pie. The New Year feast was centred round a pie from the COOP. I would take the ashet to the COOP butchers, the COOP number written in the underside, 4361, and returned a day or so later to collect the delectable pie ready to be warmed up for dinner on New Year’s Day with tatties, and peas from a tin. Followed by an apple pie and custard. Bramley apples seemed to be available all year round.

Some time in 1946 there was a big celebration in our house in Balbardie. All sorts of uncles, aunts and cousins making a night of it after a week or so of Mum baking. I suppose the makings had been hoarded but all sorts of cakes and biscuits were turned out. A cousin friendly with a COOP baker managed to get some marzipan and, up to the oxter, I wiped out the stone jar, lovely. This was the first time I had shortbread, made by Mum.

Booze and fags were important and there was an uproar in the papers with the budgets as tobacco was hit badly, enough for Dad to kick the smoking habit in 1947. He was not a drinker so was at all concerned at 1d. added to every pint of beer.

In the early 50’s my cousin Jack Smith kept pigs at the family home at Couston. He would take his horse and cart round canteens and cafes collecting brock for rendering down along with grain as slop for his pigs. Tatties would come dyed purple as not fit for human consumption. The purple disappeared on boiling! He later sold vegetables round the doors of Bathgate and Armadale. There was a great deal of fuss at that time of ham/bacon tasting of fish as pigs were being fed on fish – both waste and caught, used as cheap feeding.

A memory of Couston is reading the pre-war editions of the American magazine National Geographic with coloured advertisements of tinned hams, they looked so succulent and tasty. It was the late 50s before tinned ham replaced Spam. Big tins of Australian apricot jam did appear by the mid 50s and were so flavoursome my mouth felt it was in heaven.

By the end of the fifties things were improving and rations were a thing of the past and we could eat out. By 1961 the Roadhouse at Corstorphine offered a night of dancing with a chicken dinner for five shillings but I suppose the drinking made the profits with a Moscow Mule costing ninepence! I had to stop my girl at three. It is a casino now so probably a bit more expensive.

Food hygiene was a bit slack then and mainly was hand washing before eating. Butchers shops were slip hazards because of the sawdust laid down to soak up the blood from the carcases hanging on the rack. The man who sliced the bacon cut the cheese and made up the butter pats probably with a fag hanging from his lips! Many grocery items were purchased loose and wrapped by the grocer; bacon, cheese, butter, some flours and sugars, and eggs were never in a box. I have nightmare remembering bringing a dozen eggs from Walker’s in a brown paper bag all the way to Athol Terrace! All shopping and entertainment was done in a haze of tobacco smoke as everyone seemed to be smoking.

What we did and did not have.

There are many food items now that we did not have then or were considered suspicious.

Some things we did have but were not considered as food. Olive oil for example was kept in the bathroom cupboard along with other medicinal supplies, never as food. Our condiments were restricted to salt, pepper, vinegar, brown sauce and mustard. Made sauce was Bisto with perhaps an onion base, also added to beef mince and stew as a browning. Garlic, how French. OXO cubes came to our house sometime in the 50s and later came the other stock cubes. These were found to provide a rather nice warm drink on a cold winter night.

The only frozen food we had was ice cream from Boni’s or Serafini’s. Refrigerators did begin to appear in the 50s and freezers in the mid 60s when the Captain Birds Eye programme appeared. As there were no prepared meals available in the shops everyone needed to be able to prepare and cook their food. And they did to a better or worse standard. Schools had home economic classes for the girls. We boys were bereft of such entertainment.

We had roasted cheese; bread plain or pre-toasted and sometimes with a smidgen of onion or tomato. Later, much later, the Italians re-invented it as pizza! The lengths we went to be cosmopolitan saw Welsh rarebit and Yorkshire pudding an the menu. We did understand the English ate eels and other such items, but they were English after all. There were stories of such strange foodstuffs called curry. Were there hamburgers or hotdogs? Maybe in the wildernesses of London or Liverpool where Chinese and American cultures could be found.

Brown bread was seldom to be seen and oils were for lubrication, fat was for cooking. I remember Camp coffee substitute and it was good but coffee as such was something posh folks used and always from the bean, never instant.

Tea had always come loose in soft 1/4lb. packets, we did not know it grew in little bags. And it was always brewed brownish or sometimes black after left on the hob for hours. Green tea?

Coconuts were items from the shows at the Procession, desiccated it came in packets for cakes. Dates came at Christmas in oval boxes although the compressed variety could be sliced for a piece or baking. Very late to the menu came instant mash, pot noodles and for a while Pop Tarts. Figs and prunes we had but often used for remedial purposes when rhubarb failed.

Although we had macaroni and spaghetti they only became pasta some time in the 60s with amazement at all the various shapes. Olives were a late addition to the national menu. Apart from fish & chips and ice-cream, takeaways were an arithmetical problem. My first doughnut was from a cafe in Edinburgh sometime in the late 40s, an American (USA) addition to the menu sprinkled with white gold called sugar, what an indulgence.

Mushrooms were the province of the field gatherer as were brambles and wild raspberries. The old lime quarries up in the Bathgate Hills provided small amounts of wild strawberries.

To my generation bottled water at a price is something we cannot understand, it comes from the same taps we have in the kitchen.

Heinz was reputed to have 57 varieties but all we knew were beans until they came out with a huge surprise, tomato ketchup! We did learn some French from sauce bottles, HP I seem to remember.

Mayonnaise was foreign, salad cream was king. Sandwiches reflected the rations. There might be fish or chicken paste but seldom other meats, cheese with syboes or pickle. The smoked meat sausages from the continent just did not figure on our menu. Corned beef or spam were the only cold meats regularly on the table. Tinned fish was sardines and sometimes pilchards in an exotic sort of sauce based on tomatoes.

* * *