Life in Balbardie House

by Euan Dunsmore

December 2014.

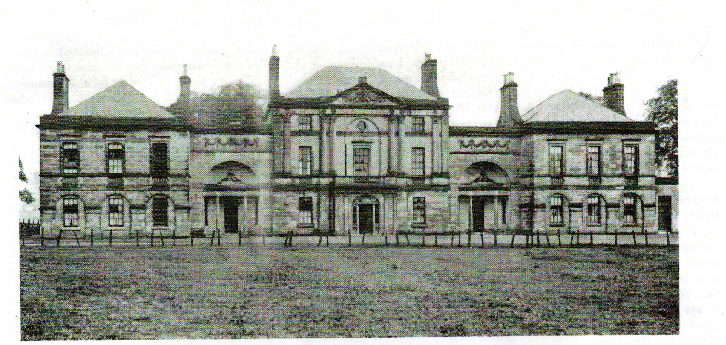

The North Front, our entrance was on the left porch and upstairs at the back.

Although my parents had a flat in Academy Street, I was born on April 7th, 1940 in my Auntie Mary’s house in Dundas Street, Bathgate. Years later my mum would enjoy telling me that there had been a late flurry of snow on that day.

My first memories are of the now destroyed Balbardie House. It was built by Robert Adam for Alexander Marjoribanks in 1793. The house was of grey West Lothian sandstone, blackened with coal smoke, with a central block and a wing either side separated with little colonnades. There was a myth that the house had been built back to front as the back looking towards Bathgate showed no colonnade but a long south-eastern facing frontage. The front faced what had once been the park complete with overgrown pond, a refuge for frogs and newts. A couple of carved stone Roman-style vases still stood in front opposite the main entrance. The main block opened into what had been a grand hallway with doors into the main rooms and a staircase to the upper floors. The park had many beech trees and a frieze of trees on what was once the estate boundary. The gable end of our block had a bottom row of mock windows properly set into the wall but painted black with white lines to represent the astragals. It would explain why the rooms were so gloomy.

The house had been modified for the tenants – miners from Balbardie Pit at first. The through-ways from wing to wing were blocked and a few toilets were fitted. Ours blocked the passage into the main block and overlooked the stone stairs where a lone gas mantle did its best to make it gloomy rather than pitch black.

We sub-let the flat or apartment from Alan Wait a tall gentleman with a tall, elegant lady-friend who would smile at me. The Wait family had been involved in shovel making in Bathgate from as early as 1890.

On our ground floor lived Mr & Mrs Jim Scally and their daughter Kathleen.

Our flat was on the upper floor, left back; three rooms with scullery. The farm yard is not shown but was separated and built on a square plan. The stack yard was between the buildings. Not shown is the cellar with the wine cellar a few more steps down and behind a normally locked door and with racks in place but empty.

Attached to the other wing was the home farm, Balbardie Mains, let to Mr Hill until he took a farm at Bughtknowes. He did not farm at Bughtknowes for long and his son Gardner inherited the farm when he was only 14 years of age. Dispensation had to be given by the school authorities to let him take up his work. I believe today he continues to farm Bughtknowes as well as an adjoining farm.

Mr Bell took over at Balbardie Mains and he had a son, Stuart. James Gribbin, Stuart and I played all around the steading, bothies and byres. It was a mixed stock and arable farm as many were in those days. The steading was a square of buildings with a main entrance facing the gable end of the big house and another out to the fields. Both entrances could be gated outside and inside making a useful trap for singling out animals for attention. In the byre was a large vicious shorthorn bull. We were well warned to keep away from its stall where it was double chained. A worse brute was the boar kept in a loose pen with an arrangement of double doors to enable transfer from one side or another to do his business. When the boar eyed you up there was intelligence looking out at you over the tightly curled tusks. He was far too dangerous to approach.

The house had seen better days and was slowly subsiding. The major cause was the extraction of the six-foot Bathgate (or Wilsontown) Main seam from Balbardie Pit a few hundred yards away. One morning when I wakened in the darkness, I found that my bed on its casters had run across the room during the night as the house settled a few inches into the ground. I got a bloody nose from striking it on the wall. We lived upstairs: a large kitchen and scullery, a very large living-room, come parents’ bedroom with a smaller room for me off to the side which probably had been a dressing room or anteroom in the glory days of the big house. The cold, draughty inside hall was shared with the Waits.

Another tenant was Sergeant Dow and his wife and I think daughter with her husband. I was in awe of the sergeant; he was a great bear of a man. One morning Mum and Dad took me down to see the Sergeant and Mrs. Dow. There was to be a send off for Eric Brown. We saw him off with his golf clubs to his first professional tournament. He was one of the finest golfers Scotland ever produced.

One day mum produced from the pocket of her wrap-around pinny a strange looking orange ball and asked me if I knew what it was. But I had no idea. ‘Well’ she said ‘you do have a treat to come. We have one and it is for a good boy.’

She took a small knife from the cutlery drawer in the Welsh dresser and began to peel the thick skin. The smell is in my nose as I type. She broke the ball into segments and the first piece popped into my waiting mouth. The flavour filled my head and I can taste it as I write and have been fond of the fruit all my days. Mum, like most of her generation, had eaten oranges and years of war shortages had not dimmed the memory. Years later the yearning look from my Mum came to mind and I had a pang of conscience because I had eaten it all. And that was the first orange of many and my favourite fruit to this day, though I also loved plums from my Uncle Andrew’s orchard at Avon Hill close to Avonbridge, and the wild strawberries from the limestone quarries up in the hills.

Fruit and other foods were rationed well into the 1950’s. As well as the basics of fats, sugars and meats, furniture and clothing were rationed. We went to Walter Bryce’s fruit and vegetable shop where the sweets were handed out for coupons. Mind you, sweeties were few indeed.

For a penny you could buy a bag of chipped fruit with the rotten bits cut out. Grocer’s shops such as Walkers as well as Woolworths sold broken biscuits in the same way and a bag of broken biscuits could be a real treat to those who had little funds and great was the joy at finding a whole one, unbroken and choice!.

Bananas came later and biting into the skin came as a shock before with a great laugh, it was taken from me by Mum and peeled for me to eat.

I am a child of rationing and dried egg and Ministry of Health (MOH) orange juice and little bottles of milk at school. Cod liver oil was, and is, vile but Scott’s Emulsion is lovely. My Dad, being a miner in a reserved heavy industry, received a few more calories than some workers. I do not remember anything much of the shortages but what child does? I do remember the fuss about sugar. I wanted just to be like my Dad and not take sugar in my tea. But as it turned out Dad had been dragooned into doing without so that ‘the bairn could have the extra’. I can only imagine the conversations about that. My cousin Jamesina worked in the prefab set up for the Ministry of Food before she moved to James Walker and Sons, grocers. The ration books were doled out in the Coop Hall and when I was a little older, I was sent to get them. Mum would leave coupons in Walkers for her butcher meat and eggs and the Coop for other goods. Close to the end of the war or perhaps just after Dad was allowed some coupons for a new soft hat. Disaster struck on Sunday on his way home from the Kirk when a strong wind blew up and his new hat was taken away over the fields and lost to sight. At first Mum was in stitches at the thought of him chasing his hat but the loss of the coupons was a blow.

Everyone had rag-rugs, home-made to patterns sold in the shops. We had a semi-circular one in black, purple, and green that lay in front of the kitchen fire as well as a great rectangular rug which took pride of place in the living room. It was a time of great pride when my Uncle Nippie Spence from Torphichen presented us with a large piece of felt. He worked in Westfield Paper Mill. Part of the process of making paper needed a great endless belt of thick felt to drain the pulp before it was carried away through the heated rollers to become paper. It was ten or more feet wide and sometimes needed to be mended or replaced. It was a great honour to have such felt in the lobby as a carpet. Everyone in the block came up to see it and it was soft and warm on the feet, so much so that it was almost a pleasure to creep out to the WC on the outer staircase.

I remember Patricia Gribben with her ringlets and her brother James as special friends. James and I would play all and every day around the big house and farmyard and over to the pit and he would walk with my Dad and me on a Sunday as we explored the Bathgate Hills. We began school on the same day, he to one and I to another; my first exposure to the religious divide. I have no memories of my parents ever making any statements on the religion of other people. My father attended the Kirk all his days but my mother never did. James had another sister, Mary and she died. It was my first time in the Chapel and I was sad as I walked with James and Patricia behind the hearse

Bairns and adults died young in the days before antibiotics. Infantile paralysis (poliomyelitis), tuberculosis, scarlet fever and diphtheria were all killers in these days. I remember Mum and her sisters speaking about the miracle cures as they came along, sulpha drugs and penicillin and M & B tablets. In the forties and fifties Bangour had a TB ward kept well away from the rest of the hospital. I lost cousins and aunts and friends to illnesses that we no longer fear. Damaged children were being condemned to a lifetime of ‘special needs’ because of measles-infected mums. The good old days? Says who? The forties and fifties saw the birth of modern medicine.

Our rooms in Balbardie House were fumigated with sulphur candles when my sister Eunice came down with scarlet fever. Eunice just remembers the loneliness of the fever hospital at Tippethill and Mum waving to her through the window of the isolation ward. She would be about three at the time.

We boys all had tackety boots which threw off sparks when we slid on the pavements. Bathgate on its hill has many paved paths and we could slide to our hearts content and our Dad’s annoyance. A common chore was to go into Woolworth’s and buy half a pound of segs. Dad would ‘re-shoe’ the boots and I would rattle away with the new armour. When the damage to boots was too much it was a walk to the bottom of the town to the cobblers who would sole and heel for a fraction of the cost of new boots. Dad would have his own boots done a little less often.

Most of our living in Balbardie House took place in the warmth of the kitchen. There was a large Welsh dresser with drawers deep enough for me to sit in and imagine boats and planes and tanks. The kitchen table whitened by daily scrubbing was where we took our meals. Up in a corner was an un-insulated copper tank for hot water although the range also had a little tank with a brass tap.

Although homely, it was a big gloomy place with one tall window at the end nearest the scullery. We had a large kitchen range fired by coal and always warm, all black-leaded and gleaming, the brass works a warm gold. Mum would tune the fire with a damper set in the chimney and at night the fire was banked up with dross.

The bathing arrangement was a large galvanised steel bath set down beside the stove with the round end set under the brass tap on the side of the tank part of the stove. Mum, being a Ure, was quite proud of her ‘Ure’ stove, ‘Made in Falkirk’. She liked to think a relative had started the place. The foundry had become Smith & Wellstood and my Uncle David Weir spent his life as a fitter making the self same stoves.

There were two gas lamps with lampshades above the range. Keeping the mantles in good shape was a never-ending battle as they were so fragile. With the dark walls, it seemed that the pale yellow light did not quite reach the sides. The quiet hiss of the gas was a comfort to me as was the one in my bedroom where I slept on an iron bed with brass knobs on. A rickety thing it was, too, with every move being squeaked out to the world. Underneath was the pot and from an early age I had to empty it in the outside toilet and if forgotten had to be done in the blackness of the night tiptoeing down through my parents room, feet freezing on the wooden floor and out into gloom of the hall. The toilet was a good number of steps over icy stone flags and inside it was as black as pitch. I have never been afraid of the dark and a good thing too.

Soon after the war, Mum lightened the kitchen walls with water-based distemper paint. After the coat of pink, she stippled in with a soft apple green to give it a lift. Stippling was by a ball of rags and I suppose nowadays it would be described as rag rolling. But it was grand after the dark green and brown décor we had suffered.

The scullery attached to the kitchen was not much more than a lobby wide enough for a gas stove and barely enough room to work around it but there was a deep sink at the window end and I could stand in it and look out over to the hills or squint over to the council housing scheme. I can see the view yet in my head. In the summer evenings, I could see and hear the men at their game of quoits in one of the gardens at the far side of the railway lines, a hundred yards or so from the house. There would be a shout as the pin was taken. On my way to school, I passed the clay pit with its centre pin and one or two of the quoits half buried in the clay. The game has more or less died out now.

At the other side of the hill and between it and an old pit bing was a little flat spot a few yards from the railway track and well hidden from any road or track. It was here that the pitch and toss school would gather on a Friday or Saturday evening. As bairns, we were tolerated provided we did not linger. It was illegal and a couple of sentries would be posted, one up on the bing and one well up the railway track to keep an eye on any suspicious bobby who might pass by. I do not know the rules but do know that the two pennies were placed on a small piece of wood before being tossed up into the air twisting and turning before hitting the ash underfoot. All heads would lean into the ring and perhaps a joyous shout ring out from a lucky winner. Much money changed hands and many a family struggled because of the loss of hard-earned pay. Miners could be fools every bit as much as the aristocracy when it came to gambling.

I suppose I was six and on school holiday in a glorious summer, all summers are glorious as a child, when with James Gribben and some help from mum and Mrs Gribben we made a kite. Some men or big boys had flown kites on the little hill close to the house and when exploring at the railway which ran to the pit we found some canes. We were well warned about the railway line, an older boy had recently lost a foot when run over by a wagon. With binder twine collected from the fences and some newspaper and flour paste and a deal of help from Mum, we made it outside on the grass at the side of the house. After a bit of experimenting with the tail we made it fly. Kite flying since has never quite captured that day at Balbardie House where James and I flew a kite in the sun.

A few days later when playing around one of the huge beech trees just off to the side of the path up to Glenmavis I fell and landed on the only stone in the sand around the base of the tree. I ran home with blood pouring from the deep cut in my knee. Mum cleaned it out and bandaged it up and cut an old sock for a cover to hold the dressing; I have the blue scar to this day. After the tears had dried, James and I went for some message or something to O’Hara’s Hut* at the bottom of the farm road into town. It was a ‘Jenny a’thing’ sort of place with bread and groceries and ginger and tobacco and a place familiar to both of us. On our way back, we spied in amongst the straggly beech trees surrounding the farm buildings an old mattress and we had great fun bouncing about and rolling around on our new toy. Eventually we tired and made for home only to be met with a screech from Mum and bundled down stairs to stand outside while she made her way to the Gribben’s house. Mum and Mrs Gribben were shocked at the state of us. We were alive with fleas. A bath was prepared on the grass and, stark naked except for my bandage, we were scrubbed clean, then the clothes given the same treatment. It was fun to see the little black specks floating in among the suds. Not so much fun were the itchy red spots. Even my sock bandage was polluted. That evening James and I enjoyed the bonfire as the mattress was incinerated with the help of some paraffin. Mr Gribben and Dad sent out to do the deed and we to watch. A great end to a great day!

Just before the road at O’Hara’s Hut, was a field where farmer Hill or perhaps Bell kept his elderly Clydesdales and we were friends with them, as they stood under another of the great estate beeches nuzzling each other. They were retired and used only for building the haystacks in the yard. They would be yoked to a line reefed through a pulley mounted to a yard on a tall central pole and attached to a grab. They would lie into the rope and swing the grab and contents to the top of a stack the size of a house. With a yank at the line the grab would open and the hay tumble out where the men would hand it into place. It would take days and always there was a picnic as Mrs. Hill or Mrs. Bell brought a great hamper of bread and cheese, fresh milk and pickles and sometimes a cooked home-made ham all for the workers. The tractor was fast becoming king of the farmyard and the horses were more or less retired. Many farms in these days had a horse or two whiling away their evening years.

We bairns ran around and got in the way and the smell of hay brings back those golden days in the stack yard at Balbardie Mains farm. Other hairsts come to mind: tattie howking by men, women and children in the top field backing onto Torphichen Road with the work ending only when the frost began to settle on the field under the moon. In the big field that is now the Belvedere housing scheme, James and I would try to stook newly cut corn, the sheaves as big as ourselves and they would not stand for us. Men stood around with terriers ready to take a rabbit or two as the last cut was taken from the centre of the field.

We had a washday at Balbardie House. In the washhouse down close to the farm were a number of coppers fired by coal, a great big mangle close to the door and a supply of scrubbing boards. Mum preferred the glass type as with the galvanised one the zinc would wear out and the board would become rusty. The washhouse was built on similar lines to a byre with a central ditch to act as a drain for the coppers when all washing was done. When two or three of the women were washing together, it was a warm and steamy place to be with the slosh of wet clothes into wooden tubs and the dragging across the floor to the mangle with the big hand wheel and open gears.

I remember the 1947 winter as a fairyland of snowdrifts and sledging on the hill close to the house. My school in Mid Street was closed for a week. We were snowed in with a huge snowdrift at the front up to the bottom of the upstairs windows. Because of a freak of the wind, there was a space wide enough for a man to squeeze down the edge of the building. All the men in the building turned out to cut a path through to the farm road. It was like a railway cutting with the men on different ledges cutting the way through. Later they mustered to clear the flat leads between the main block and outer wings of the house. Snow had piled up and was turning into ice and I suppose now threatening the flat roof with weight. Great lumps of ice were thrown to the ground to relieve the weight. It was great fun for us kids but must have been pure misery for the adults.

As we grew older, Dad walked James and me around the hills and we explored further afield. We went beyond the pit along Torphichen road and to Macnab’s Distillery with its old set of rails and one bogie.

Balbardie Pit with its great tall chimney did not produce coal, or very little, and its primary purpose was as an emergency exit for Easton Pit. A steam train would run to it on occasion. Once it de-railed across the field from the front of the house and everybody turned out to watch as it lay on its side spitting steam. We could make our way into the boiler house of the pit with its row of Scotch boilers and look around. There was a large receiving vessel just outside the doors of the boiler house. It had an opening on top we could look into. The whole place could have been a death trap to bairns and I never ever saw anyone in the place despite their being a couple or more of the boilers under fire. The older red bings on the Torphichen Road side ran for several hundred yards and were a playground every much as the fields and the pit yard.

Come November 1949 and we moved to a new council house in Athol Terrace complete with electric light. A new style of life with a gift of new friends to play with as we explored the Bathgate Hills and Macnab’s Pond in the Glen.

James and me went our different ways and over the years we have met and we are friends to this day.

* O’Hara’s Hut was definitely at the top of Dundas Street to the entry to Balbardie. It was painted council-house green and occupied by a wee woman with a bun hairdo, iron grey in colour. And nary a smile. It was still there when my Auntie Jenny moved into her house there in Belvedere. My Gran spent her last days in her house.

The exit to the Torphichen road was protected by a house probably the gate keeper’s originally when built. The distillery faced the Gatehouse.

There was a house on the Torphichen Road at the junction with the road to Ballencrief Farm. There were a few steps up to it and I am not sure if it was a proper shop but on occasion Dad would get some sweets for our walk round the hills.

The rear of the house with its main block and two connected pavilions. We were in the top right. My bedroom on the extreme right. Only two of the windows on the ground floor were real. The others were false. The tenants each had a small garden on this side of the house where tatties and leeks and onions and other vegetables were grown. I do not think any were for flowers.