The Hilderston Silver-mine

from The Rocks of West Lothian

by Henry M. Cadell 1925

p360

Stephen Atkinson, in his Historie of the Gold Mynes in Scotland, written in 1616 gives a detailed account of the Hilderstone mine:

Sir Bevis Bulmer hath sett downe in his booke, the manner how the rich silver Mynes at Hilderstone in Scotland were found. It was found out by meere fortune or chance of a collier, by name Sandy Maund. This Scotsman by means of digging the ground, hitt upon the heavy peece of red mettle. (This is niccolite or copper nickel – nickel arsenide NiAs It is sometimes called kupfernickel or devils’ copper.) It was raced with many small stringes, like unto haiers or thredds. It had descended from a vaine thereof, where it had engendered with with the sparr-stone called cacilla (calcite?). And he sought further into the ground, and found a piece of brounish sparr-stone, and it was mossie. He broke it with his mattocke, and it was white, and glittered within, like unto small white copper keese. And he never dreamed of any silver to be in that stone and he showed it to some of his friends; and they said ‘Where hadst thou it?’ Quoth he, ‘At the Silver bourne, under the hill called Kerne-Popple.’ Whereupon a gent of Lyhcoo, wished Sandy Maund to travaille unto the Lead-hill, and about Glangonner water he should hear of one Sir Bevis Bulmer, and said, ‘If it prove good he will be thankefull.’ Whereupon, he took his journey towards the Leadhill, and came to Mr Bulmer’s house, and shewed these few mineralls, or minerall stones he had gotten at the Silver bourne near to Lythcoo. Then one of his servants made fier in the assay-furnace to make triall thereof. Mr Bulmer did not trust to the first triall, because it proved riche; but went to it againe, and againe, and still it proved rich and wondrous rich.

Shortly after I was brought thither, the silver myne being sett open, I was stricken downe into the shaft called God’s Blessing; and I brought up with me a most admirable peece of the cacilla stone, a minerall stone, which me thought came from one of God’s treasure houses.

The manner how it grew was like unto the haire of a man’s head and the grasse in the feilde. And the vaine thereof, out of which I had it, was once two inches thick, by measure and rule: the mettle thereof was both malliable and toughe. It was course silver, worth 4svid the ounce weight; not fine silver as is made by the art of man.

The greatest quantity of silver that ever was gotten at God’s Blessing was raised and fined out of the red-mettle; and the purest sort thereof then conteyned in it 24 ounce of fine silver upon every hundred weight; vallewed at vi score pounds starling the ton. And much of the same red-mettle, by the assay, held twelve score pounds starling per ton weight… Until the same red-mettle came unto 12 faddomes deepe, it remained still good; from thence unto 30 faddome deepe it proved nought: the property thereof was quite changed miraculously in goodness..

It is clear that the lode contained, in addition to the argentiferous galena and red ore, some native silver which is much rarer and far more precious. This is probably the only recorded occurrence of native silver in Scotland.

Sandy Maund, who was probably a coal miner at Hilderston or Kipps, found the silver ore in 1606. The proprietor of the land was Sir Thomas Hamilton of Binnie and Monkland, the King’s Advocate. In January 1607, after hearing of the discovery, he took a lease from the King of all the minerals in the district, including those on the lands of Ballencrieff, Bathgate, the Knock of Drumcross, Tartraven, Torphichen, and Hilderston. The landowners, especially James Ross, the laird of Wardlaw and Tartraven, did not relish having miners on their properties.

After the silver-mine had been working for a few months it showed every sign of prosperity, and from a report made by the Lord Advocate to the Privy Council in March 1607, the profit was estimated at £500 sterling per month. No doubt, thinking of the national good, James VI nationalised the mine on 8th May 1608. Hamilton was given £5000 as compensation. When Sir Thomas handed over the mine he left a large heap of ore on the ground, and it appears that this and the ore that was raised was mostly taken down to ore dressing and smelting or fyning works on the shore of Linlithgow Loch.

Cornishmen and other English miners were brought in from time to time. Twenty-six pickmen were at work in May 1608, and of these seven were employed on the day shift, and seven at night in producing ore in the single shaft – probably the Blessing. The remaining twelve were engaged in opening up new shafts. Thirty-three oncostmen were engaged in various tasks including raising ore and water. In October 1608 the King brought from Saxony, seven miners and a skilled metallurgist called Henry Starchy or Starkie. For centuries, Germans had been working silver-mines in the Harz Mountains and Erzgebirge.

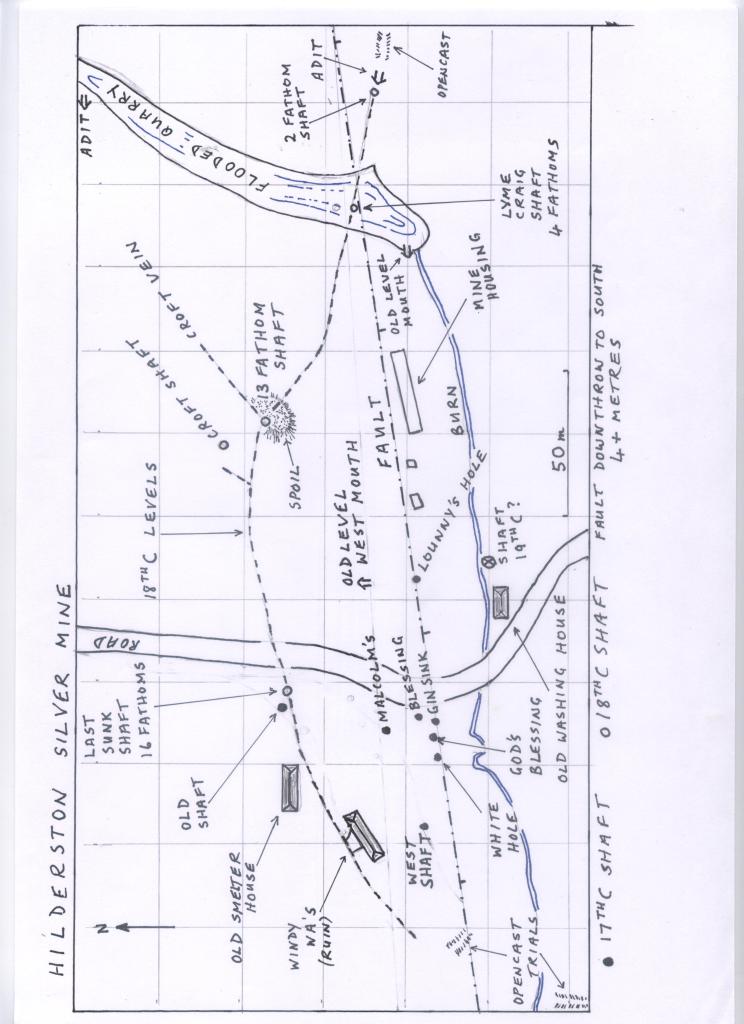

The Hilderston mine had at least seven shafts, three of which were sunk by the Germans. The shafts had the following names:

- Blissing Shaft also called Grace and Benison

- Germans West Shaft

- Germans East Shaft

- Harlies Shaft

- A new shaft set set down by David the German callit – Serve them all

- Mention is also made of a Long Shaft and the Blak Shaft.

Thirty-five Englishmen arrived in September 1608. There were no dwellings at the mine so they had to lodge at Linlithgow.

It is said that after the mine was nationalised it never earned 5s. more profit. In March 1613, the King let the mine out to Sir William Alexander of Menstrie, Thomas Foulis, goldsmith of Edinburgh, and a Portuguese called Paulo Pinto. They could make little of it. Operations ceased soon after 1614.

Sir Thomas Hamilton was the only one who did well from the mine. He became Lord President of the Court of Session in 1616, was created Earl of Melrose, and afterwards Earl of Haddington. In Edinburgh he was known as Tam o’ the Cowgate. He died in 1637.

[From:

Mining Silver in the Bathgate Hills – West Lothian Council Libraries, Local History Library

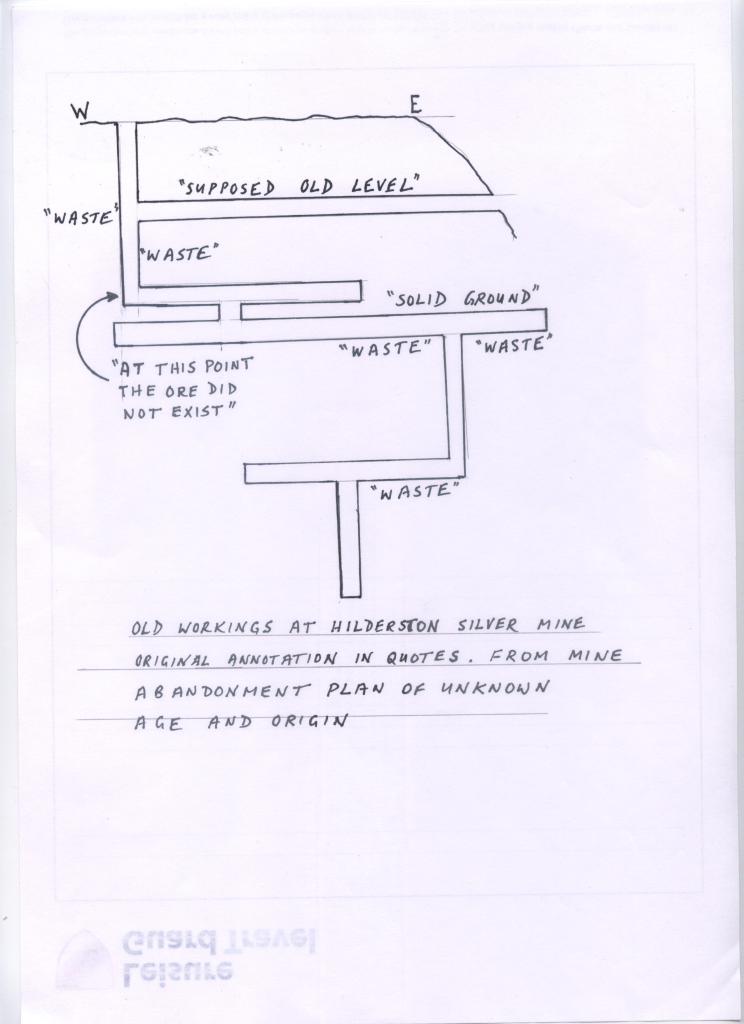

For some 150 years, the mine at Hilderstone lay undisturbed. The mineral rights had been acquired by the Earl of Hopetoun, but it was 1766 before his successors re-opened the mine. The 18th century miners found that the vein of silver had been worked out, but they mined the lead ore for a few years. In 1772, when nothing of value remained, the mine was closed up again.]

Nothing was done till 1870 when Henry Aitken of Falkirk reopened the mine. He obtained leases from the Earl of Hopetoun and Mr Andrew Gillon of Wallhouse. No silver had been found by 1873. In some of the old workings niccolite (red-mettle) had been found. (Much of this had been raised and discarded because it had no value in the early 1600s.) Fresh nickel ore fetched £4 13s. per cwt so the mine had a prospective value for its nickel. (Niccolite is poisonous and it is recorded that local hens died after scratching about at the mine mouth.) In 1873, a shaft was sink to a depth of over 220ft. but this found no more silver or nickel. In 1896, the old Blessings shaft was cleared out and the ancient workings were exposed to view. Mr Aitken had no further success with his project so he gave up in 1898.

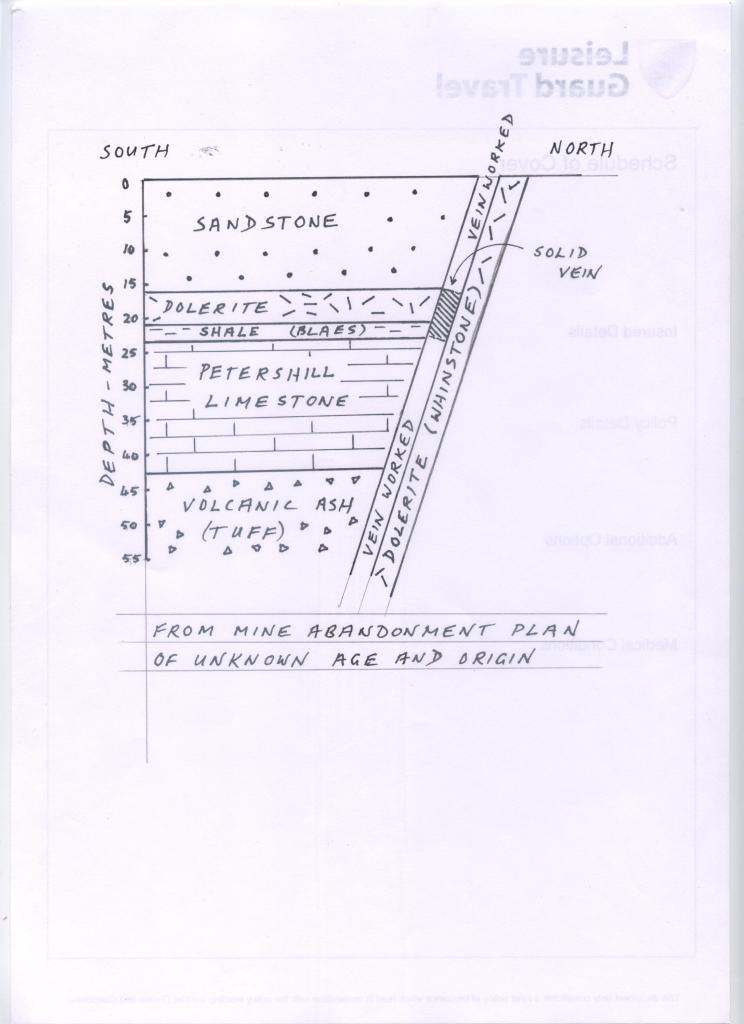

During this last exploration Mr Aitken invited me to go down with him for a look at the vein. The vein was in a fissure alongside of or near a small basalt dyke, apparently a branch eastwards from the well-known dyke of the Knock, which has a northerly trend and cuts through the Petershill Limestone and the lavas above it.

The reef was at places 6ft. wide and the gangue was heavy spar or barytes. It did not retain this thickness very far from the shaft, and pinched out until the walls were less than 1ft. apart. I got stuck hard and had to be pulled out by Mr Aitken. The walls were all minutely grooved, showing that hammers and chisels or small picks had been skilfully used. It is interesting to note that before explosives were used the old method of blasting with limeshell was in vogue. Holes had been drilled and filled with lime , and some of these had been miss-fires and remained to show the ancient but very safe style of splitting rock.

Mr Aitken gave this rock sequence found in sinking a new shaft:

| Rock | Feet |

| Surface, clay and stones | 18 |

| Sandstone | 11 |

| Fakes (shaley sandstone) | 37 |

| Whinstone | 16 |

| Blaes (carbonaceous shales of a bluish colour) | 11 |

| Petershill Limestone | 54 |

| Volcanic ash | 42 |

| Volcanic ash and whinstone | 36 |

| Volcanic ash found in bore from base of shaft | 360 |

| Total depth explored | 585 |

From:

LOTHIAN GEOLOGY An Excursion Guide

Hilderston Mine: Silver-Lead-Zinc Mineralisation

The mine was in operation initially from 1606 to 1614 but made little or no profit after the first two years (i.e., after it had been nationalised by James VI.). The silver occurred as filaments in a vein along with baryte and niccolite. The vein was located on the margin of a thin E-W dolerite (whinstone) dyke which cut sandstones and siltstones above the Petershill Limestone. The economic vein extended for only 80m to the east of the N-S dyke /sill and for 18m below the surface. In the 18th century the mine was reopened and worked for lead and zinc which occurred with baryte and calcite at a deeper level where the vein cut the Petershill Limestone. A second, much longer vein, some 60m to the north, was also worked at this time, but this phase of working ceased in 1772. The original workings were re-excavated during the period 1865 to 1873 using money from the sale of niccolite and again from 1896 to 1898. However, no further economic deposits of silver or lead were discovered.

The minerals found in the mine are shown in the table:

| Mineral | Composition |

| baryte | barium sulphate BaSO4 |

| calcite | calcium carbonate CaCO3 |

| dolomite | calcium magnesium carbonate CaMg(CO3)2 |

| quartz | silicon dioxide SiO2 |

| galena | lead sulphide PbS |

| sphalerite (zinc blende) | zinc sulphide ZnS |

| niccolite | nickel arsenide NiAs |

| erythrite (cobalt bloom) Bloom:- The mineral occurs as an efflorescence like salt coming to the surface of brickwork. | hydrated cobalt arsenate Co3As2O8.8H2O |

| annabergite (nickel bloom) | hydrated nickel arsenate Ni3As2O8.8H2O |

| bravoite | iron nickel sulphide FeNiS2 |

| pyrite | iron sulphide FeS2 |

| chalcopyrite | copper iron sulphide CuFeS2 |

| albertite | bitumen (solid hydrocarbon) |

| silver |

From:

The Mineralogy of Scotland

By M. Forster Heddle 1901

Volume 1

P9 Silver

Was obtained in the year 1606; it was first found imbedded in a knitted form in niccolite at the silver-lead mine at the north-east foot of Cairn-naple Hill, the highest of the Hilderston Hills.

Below a depth of 12 fathoms the niccolite was still got in quantity but it was no longer argentiferous, though ‘unaltered in colour, fashion and heaviness.’ So long as the niccolite carried silver the profit from the mine was £500 per month. The galena (lead sulphide) associated with the niccolite was argentiferous to the extent of ¾ oz. to the hundredweight. The niccolite also occasionally carried native silver in cavities.

P16 Galena

At the silver mine , Cairn-naple, imbedded in barytes

P25 Niccolite

Found at the Hilderston Hills in a vein of barytes, cutting limestone at the east base of Cairn-naple. The vein minerals are barytes, native silver, annabergite, erythrite . blende, galena, pyrite, and brown spar (dolomite rich in iron).

In a letter of Sir Richard Martyn to the lords of His Mayesty’s Secret Council, of date Oct. 1608, he seems to refer to niccolite, when he writes:

It is held that there is in ye Scottish ure, (ore) a substance of a matter which some call a marquisit, and, and other some an arsenick, and others a sulphurous matter wch houldith the silver…

But the nature and value of the niccolite was never recognised during the time this mine was first worked. It was all lost in extracting from it the filamentous native silver which, to a depth of 12 fathoms, it contains.

Sir Beavys Bulmer or Bilmour was in May 1608 appointed ‘maister and surveyair of the earth works of the late discouerit siluer myne,’ discovered by Sir Thomas Hamilton of Bynnis, King’s Advocate, the proprietor.

During the short period when the mine was worked about 1870 a considerable quantity of niccolite was got, having been used along with barytes to fill up the old drifts. This was all sent to Germany and was called platinum in the neighbourhood of the mines. Only small quantities of annabergite are now (1893) to be found. The ore got between 1870 and 1873 was incorrectly called ‘an arsenious sulphuret of nickel,’ instead of a sulphurous arsenuret. It was said to contain about 30% of nickel, and 2% of cobalt.

Volume 2

P163 Erythrite

Occurs as a peach-blossom red chalky-looking encrustation in the lead-veins at the Silver Mine at Cairn Naple, in the Bathgate Hills.

Annabergite

Colour apple-green to greenish-white. Occurs also in the Silver Mine at Cairn Naple

P170 Vein Barytes

LINLITHGOWSHIRE. Hilderston Hills, at Cairn Naple, associated with niccolite (Fleming). [On p169 it says that John Fleming also described vein barytes in Fair Isle.]

From

Natural Environment Research Council

Institute of Geological Sciences

Polymetallic Mineralisation in Carboniferous Rocks at Hilderston, near Bathgate

By D. Stephenson

Summary

Five boreholes in the vicinity of the ancient Ag-Ni-Pb mine at Hilderston, near Bathgate have yielded new geological information. These results, together with a critical re-examination of old records, are interpreted in relation to an ancient environment of a volcanic island with a coastal lagoon and fringing reef deposits. Zn-Pb mineralisation occurs in the lower, clay-rich part of the Petershill Limestone, which was deposited in an anaerobic lagoon on the edge of a volcanic landmass during the Lower Carboniferous Epoch.

The best bore-hole intersection shows 8 m of mineralised limestone, with underlying

carbonaceous mudstone (1 m) and volcanic ash (2 m), having an average concentration of 0.14 % Pb and 0.66% Zn and maximum values of 0.6% Pb and 3.1%

Zn in the carbonaceous mudstone.

Late-Carboniferous ore veins occur within the Petershill Limestone and in immediately overlying clastic (sandstone, siltstone and mudstone) sediments, where they are cut by E-W faults and dolerite (whinstone) dykes. At Hilderston Mine two assemblages are recognised in the vein:

- Ba-Fe-Ni-Co-Ag-As on a dyke margin adjacent to the clastic sediments

- Fe-Pb-Zn-S at lower levels adjacent to the limestone.

Zones of alteration in the dolerite dykes carry hydrocarbons and weak Ba-Fe-Cu-F mineralisation. No potentially-valuable vein deposits were discovered in the present investigation

General Geology

The Petershill Limestone, formerly exposed in the NNE line of quarries, is overlain

by a massive sandstone at about the present water level, followed upwards by a series of shales, siltstones and sandstones with a few interbedded tuffs. This succession

dips to the west-north-west at about 18 to 20o and is overlain by a thick sequence of basaltic lavas. A 40 m wide N-S dyke of quartz-dolerite is inclined to the east at

about 60o.

The E-W Hilderston Fault carried the original silver vein and so provided a control for the mineralisation. It is a normal fault with a throw to the south of at least

4 m. A thin E-W dolerite dyke, which may or may not be an offshoot from the wide,

N-S dyke occupies the fault plane in the old workings. The silver vein occurred on the south side of this E-W dyke and appears to have terminated westwards at the N-S dyke. Eastwards, the fault continues as a mineralised breccia, but the E-W dyke dies out and there are no workable deposits. It seems that the vein was restricted laterally within the fault plane to the extent of the E-W dyke, and vertically to the succession between the top of a major tuff unit and the base of the overlying basalt pile.

Genesis of ores

The depositional environment of the Petershill Formation would seem to be ideal for the accumulation of metalliferous minerals. The formation was deposited in a shallow shelf sea fringing a volcanic landmass and represents a relatively short quiet period within a very active volcanism. The rocks between the Silver Mine and North Mine Quarry were deposited in a shallow coastal lagoon. Anaerobic conditions with restricted circulation are indicated by the dark, clay-rich limestones with shell debris and algal structures replaced by iron sulphides. It is also reasonable to suppose that the rate of heat flow was high in the area at the time of deposition, manifested by intense and prolonged volcanic activity and possibly associated with a large intrusion at depth, now seen as regional magnetic and gravity anomalies close to the Bathgate Hills. If the strata accumulating in the area were sufficiently permeable, it is likely that convective cells, generated by the high heat flow, could circulate mineralising solutions throughout the permeable succession. The source of the mineralising solutions is always a matter of great debate. In a marine environment the possibility always exists that seawater may be circulated. Alternatively, mineral-rich brines may have been squeezed out of the underlying the Oil-Shale Group.

Assuming that brines existed and that a mechanism was available to circulate them, it is now necessary to consider the origin of the metals. It is unlikely that they may have been derived directly from the volcanics themselves. The simplest explanation seems to be that they have been carried by brines from the oil-shales. Unfortunately, trace element data is not available for the Lothian oil-shales but elsewhere the association of ores with hydrocarbon-bearing sedimentary sequences and the presence of Fe-Zn-Pb sulphides ( + Ba and Cu) in oil reservoirs, is well-established. It is also recorded that oil-shales are enriched in silver relative to other sediments.

The origin of the sulphur cannot be determined with any certainty. The close proximity of active vulcanicity would ensure a supply of primary sulphur, and sulphate, dissolved in sea water would be readily precipitated by biological reduction in the oxygen-poor environment of the coastal lagoons. Although the underlying oil-shales have a high sulphur content, metallic sulphides are very insoluble and mineralising fluids in general are sulphur deficient. It therefore seems likely that the metals were transported as soluble chlorides and combined with sulphur from a

separate source at higher levels.

From the above discussion it is possible to propose a tentative model:

High heat flow during the Lower Carboniferous, possibly associated with a deep

seated igneous body, gave rise to intense volcanic activity centred upon the present Bathgate Hills. Convection currents were generated within the rocks involving water squeezed from the oil-shales and possibly downward-circulating sea water. Mineral-rich brines were expelled onto the floor of a coastal lagoon. There they formed pools in a calm, reducing environment and reacted with sulphur in the sea water and sediments around the volcanic landmass to form sulphides within the clay-rich carbonates which were precipitated in the lagoon.

Silvermine Borehole – Inclination 44o

| Depth to base of rock m | Rocks | Mineralisation |

| 2.91 | Peat | |

| 7.29 | Boulder clay | |

| 12.00 | Silty mudstone and siltstone | |

| 13.11 | Mudstone | |

| 14.35 | Volcanic ash (tuff) | |

| 16.77 | Sandstone | |

| 17.20 | Interlayered sandstone and siltstone | |

| 18.75 | Sandstone | |

| 19.69 | Tuff | |

| 21.50 | Silty mudstone | |

| 23.95 | Mudstone | |

| 25.55 | Major fault zone. Mostly carbonate-rich vein material with only small patches of brecciated (broken) wall-rock. Below 24.6m most of breccia fragments are limestone. Sharp margin at base. | Starts with a sharply defined band, 3cm wide, which is 30% pyrite. Ironstone is heavily impregnated with calcite veins to 2cm thick. Cavities to 1cm wide contain calcite and black hydrocarbons, often with much pyrite and a little chalcopyrite. A mass of calcite from 24.88 to 25.32m has many large cavities. |

| 45.37 | Petershill Limestone | Some thin calcite veins and small patches of dolomite. Small fault at 26.00m contains thin calcite veins. Breccia with calcite from 29.27 – 29.37m. Near base of limestone some small specks of pyrite Also, some nodules of pyrite (diameter 1cm). |

| 46.15 | Mudstone | Specks of pyrite |

| 47.45 | Sandy volcanic ash | Pyrite common |

| Volcanic ash (tuff) | Pyrite present along with calcite veinlets. Some veinlets contain pyrite. | |

| Base of borehole 55.02m | ||